Spiritual Awakening – Honey, Vinegar OR Chocolat

I’ve been mulling over spiritual awakening in my morning meditations this a.m.. How does it arrive? Where does it come from? What awakens our own hearts and the hearts of our neighbors to the ways of Jesus?

I’ve been mulling over spiritual awakening in my morning meditations this a.m.. How does it arrive? Where does it come from? What awakens our own hearts and the hearts of our neighbors to the ways of Jesus?

Favorite chair, cup of coffee in hand (Loving Community mug of course) and listening to the ambient sounds of nature by German artist Hari Deuter (thanks to Pandora). Saturday mornings are a soulful time for me.

I know other early risers as well. One is my east coast friend Laura Hairston. She often posts from what she is learning and reading.

Today she reminded me of an epic quote from The 2000 film Chocolat, a comic fable adapted from a novel by Joanne Harris, which tells the story of sweet spiritual awakening in a quiet and spiritually dull village in the French countryside in 1959.

In the film’s breakthrough moment, Father Henri, the young and lovable village priest finds his voice in his weekly sermon and proclaims to the repressive and burdensome church and village elders…

”I don’t want to talk about his [God’s] divinity. I’d rather talk about his humanity. How he lived his life here on earth – his kindness, his tolerance. Here’s what I think – we can’t go around measuring our goodness by what we don’t do, by what we deny ourselves, what we resist and who we exclude. I think we’ve got to measure goodness by what we embrace, by what we create and who we include.”

”I don’t want to talk about his [God’s] divinity. I’d rather talk about his humanity. How he lived his life here on earth – his kindness, his tolerance. Here’s what I think – we can’t go around measuring our goodness by what we don’t do, by what we deny ourselves, what we resist and who we exclude. I think we’ve got to measure goodness by what we embrace, by what we create and who we include.”

AMEN! ~ You’ve probably heard of the old adage, “You can catch more flies with honey than vinegar.” This is that! — Psalm 34:8 (NLT) reads, “Taste and see that the LORD is good. Oh, the joys of those who take refuge in him!”

Today I choose to reflect the goodness of God, embrace what he has created, and invite and include others to taste and see that the Lord is good!

Live humbly and kind,

Jim

PS – Want to read more about Chocolat? Are you an Enneagram fan? Below is a reading from Father Richard Rohr from 2007 recounting the movie in detail and how it relates to the Enneagram One Archetype.

Reprinted from Radical Grace, Vol.20, No. 1

January-February-March 2007

A Publication of the Center for Action and Contemplation

CAC Founder, Richard Rohr, OFM

Email: [email protected]

The 2000 film Chocolat, a comic fable adapted from a novel by Joanne Harris, tells the story of sweet spiritual awakening in a quiet village in the French countryside in 1959.

The imperious village mayor, Comte de Reynaud, is a pious and principled man, wonderfully played by Alfred Molina. “The Comte was a student of history [who] trusted the wisdom of generations past. Like his ancestors, he watched over the little village and led by his own example. Hard work, modesty and self-discipline.”

The Comte is a classic Type One Enneagram character – variously known as the Teacher, the Crusader, the Moralist, the Perfectionist. Ones are generally principled, purposeful and self-controlled. The Comte de Reynaud is a man on a mission to protect and maintain the virtue and morality of his village. Being fixated in his egoic Enneagram trance, however, he has a burdensome sense of personal responsibility and obligation, feels it is his job to correct and improve every stray situation and wayward soul in his jurisdiction, and is inclined toward impatience and intolerance when it comes to matters of human frailty.

The season of Holy Lent is upon the village, — “A time of abstinence and reflection and sincere penitence.” The good mayor has dutifully forsaken the pleasure of all things sweet – refusing even a drop of honey for his tea or a spoon of preserves with his crust of bread. When he has a mild dizzy spell in the presence of his office assistant, Caroline, she asks if he has been eating properly. “My fast has been very strict this year, but how can I make demands of the townspeople if I don’t demand more from myself?” Conscientious Ones lead by example and dutifully embrace hardship and sacrifice in the name of a good or just or holy cause. Unfortunately, they often set unrealistically high standards of perfection for themselves and others, which can lead to frustration and failure.

As the church bells toll on a Sunday morning, two strangers arrive in the quiet village. Vianne Rocher and her young daughter, Anouk, have taken a lease on the vacant patisserie in the town square across from the church. The inquisitive Mayor soon pays them a visit, inviting Vianne and her daughter to Mass to worship with the townsfolk.

He discovers, to his dismay, that not only are the newcomers not churchgoers – “But we love being so near the sound of the bells, don’t we Anouk?” — but Vianne is an unwed – and seemingly unrepentant — single mother. More alarming yet, she plans to fix up the old bakery and open a chocolate shop in plain view of the church — during the holy Lenten fast. “I could imagine better timing,” says the disapproving Mayor.

Vianne, played by Juliette Binoche, is a charming, free spirited woman, the embodiment of a warmhearted Type Two Enneagram character – the Caretaker, the Altruist, the Special Friend — who lives to serve and nurture others while sometimes neglecting her own deepest needs. Once theChocolaterie Maya opens for business, Vianne overcomes the skepticism and resistance of the villagers one by one as they succumb to the mouthwatering magic of her chocolate truffles, hot cocoa and cakes. She disarms and charms each customer with her caring, interpersonal style. In splendid Two fashion, she intuits each person’s hidden need or secret desire and prescribes the perfect chocolate potion.

With her attention to matters of the heart, Vianne arouses many neglected appetites. She successfully prescribes a chile-laced chocolate truffle to “awaken the passion” in a discontented couple’s stale marriage. She reunites an artistic young boy with his lonely and estranged grandmother by arranging for him to draw her portrait over steaming cups of cocoa. She brings together the shy but smitten elderly dog-walker with the still-grieving World War I widow. She later rescues a battered housewife from her loutish, hard-drinking husband, taking her in and teaching her how to turn chocolate into glorious works of edible art.

Soon the parishioners are showing up at the confessional with stories of lapsed will and broken fasts. They dutifully describe their sinful pleasures in mouthwatering detail to the hapless Pére Henrî, the novice young priest recently arrived at his village post.

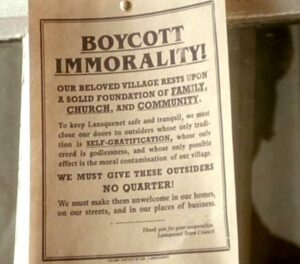

Meanwhile, the good Mayor, alarmed by the escalating consumption of sweets and rampant disregard for Lent, becomes increasingly aggravated and adversarial, zealously embarking on a mission to put Vianne out of business before Easter.

Ones characteristically have problems with repression and resistance. Scrupulously self-controlled, fixated Ones repress their instinctual impulses and inhibit their natural human desires in a misguided attempt to be ‘good’ – as they struggle to live up to their Inner Critic’s ruthless ideals of moral perfection. And they generally want to take their ‘flock’ with them.

Appealing to their comfortable, inherited prejudices, the Mayor tries to turn the villagers’ moral judgment against Vianne. “Shameless, isn’t it? The sheer nerve of the woman – opening a chocolaterie just in time for Lent. The woman is brazen. My heart goes out to that poor illegitimate child of hers.”

De Reynaud also calls on the young Pére Henrî, (discovered performing an animated rendition of Elvis’ “You Ain’t Nothin’ But a Hound Dog” while raking the church grounds), advising him to investigate the goings on at the Chocolaterie. “It’s important to know one’s enemy.” Each Sunday the beleaguered Pére Henri is obliged to deliver a sermon heavily edited and reworked by the Mayor — “I’ve looked at your sermon and I’ve made one or two notes……” — dutifully charging the parishioners to “resurrect their moral awareness” and resist wicked temptation. To the continued consternation of the Conte, the grave Sunday sermons are punctuated by the sound of candy wrappers crackling in the pews.

Despite his earnest efforts, the Comte finds himself losing his crusade against Chocolaterie Maya, although he remains resolute in his own quest for moral perfection. Working feverishly on Pére Henri’s sermon the day before Easter — “Leave it with me. We want it to be perfect tomorrow.” — he sees from his window his devout assistant (and unacknowledged love interest) Caroline coming out of the forbidden chocolate shop. He realizes he has failed utterly to coerce the good people of the town into renouncing Vianne and their newfound sense of pleasure and delight. He falls to his knees in prayerful despair. “All my efforts have been for nothing. I’ve suffered willingly for weeks — Sorry, my suffering is nothing. — I’m lost. Tell me what to do.”

His sense of disillusionment, futility and failure, and the lack of support for his rigid sense of morality, trigger the Comte’s downward spiral into unbearable frustration and rage. That evening, wielding a long knife, he breaks a basement window and enters the chocolate shop. He climbs into the front window display, which is overflowing with ornately carved chocolate creations, bowls of candies and fudge and truffles, and big luscious chunks of chocolate. The distraught Comte throws himself into an impassioned frenzy of destruction, violently hacking away at the offending chocolate.

In the tumult, a bit of chocolate splatters across his lips. He tastes the sweet temptation. Before he can restrain himself, the years of long-suffering, rigorous self-denial erupt with volcanic force. His pent-up desires burst to the surface. He loses himself in a Dionysian orgy of pure chocolate indulgence. Moaning in pained ecstasy, he stuffs his face with gooey chocolate, gorging uncontrollably on the forbidden sweets. He passes out in the window box.

As Easter morning dawns, he is discovered by Pére Henri, face down in the ruined window display, his whole body disheveled and smeared with chocolate. He awakens to see Vianne offering a glass of tonic water. “Drink this – it will refresh you.” The Comte is mortified beyond words, expecting to be condemned for his malicious act, ruined by his own mortal fall into disgrace. But he sees in Vianne’s eyes only compassion and kindness, and in the truth of that blessing he finds his own heart, humility, and humanity. “I’m so sorry,” he says. She smiles. “I won’t tell a soul.” Then he realizes – “It’s Easter Sunday. I didn’t finish the sermon.” “I’ll think of something,” Pére Henri says.

Pére Henri delivers his own heartfelt Easter sermon to the villagers, as the redeemed Comte, bathed in a new-found serenity — the Virtue of the One — listens attentively. “I’m not sure what today’s theme should be. Do I want to speak of the miracle of our Lord’s divine transformation? Not really, no. I don’t want to talk about his divinity. I’d rather talk about his humanity – how he lived his life here on Earth – his kindness, his tolerance…. Here’s what I think. We can’t go around measuring our goodness by what we don’t do – what we deny ourselves, what we resist and who we exclude. I think we’ve got to measure our goodness by what we embrace, what we create, and who we include.”

And so it went. The parishioners “felt a new sensation that day – a lightening of the spirit – a freedom…. Even the Comte felt strangely released — although it would take another six months before he worked up the nerve to ask Caroline to dinner.”

And Vianne, who had been preparing to leave the village in compulsive pursuit of her next rescue mission, was herself moved to give up her wandering ways and acknowledge her own deep need to put down roots, to foster lasting friendship and raise her daughter in a stable community. “The wind spoke to Vianne of towns yet to be visited, friends in need yet to be discovered, battles yet to be fought — by someone else next time.”

There are many delights and pleasures to be had in viewing the film Chocolat. If you have a sweet tooth, you just might want to indulge it.